One hundred days that shook the world

KEY MESSAGES:

- In 100 days, Donald Trump has raised tariff barriers to a level not seen in a century

- Trade between the United States, China, Europe, and the rest of the world has been disrupted

- The uncertainty shock is weighing heavily on household and business morale

- Faced with the negative reaction of financial markets, the US administration has retreated slightly

- The risk of a global recession has moderated somewhat but remains higher than normal

Before Donald Trump began his second presidential term, everyone knew his intentions. He had spent the election campaign hammering home his ambition to raise tariffs, cut taxes, axe staff in the federal administration, deregulate and combat illegal immigration. All these things were already close to his heart during his first term. The difference is that his victory in 2024 was broader than that in 2016 and his teams seemed better prepared to deliver the MAGA agenda by applying the ideas of conservative think-tanks.

What was unclear at the time was the sequencing, intensity and application method of these policies. Under “Trump I”, the first year was dedicated to tax reform, the following two years to the trade war with China and the final year to dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. One hundred or so days after the inauguration, we have a better idea of “Trump II”.

The sequencing: the tariff war first and foremost. In this area, the US president has employed emergency powers allowing him to take multiple decisions outside any institutional or political safeguards. As such, he can announce tariffs, suspend them, announce new ones, postpone them again, and so forth. Who can believe this tariff obsession will ever come to an end? The next step will be the tax question, on which the president cannot circumvent Congress. The Republicans have a thin majority in the House and Senate, but there remain disagreements between them about the scale and duration of tax cuts and compensatory measures to be taken on the spending side to prevent the cost from becoming exorbitant. Since the federal debt is high and long-term interest rates have risen, this is a sensitive subject.

The intensity: the most maximalist option in campaign meetings has prevailed. When Trump advocated a 10% tariff on the world and a 60% tariff on China, this looked like the worst-case scenario. It is now more or less the most realistic option. Relative to the extravagant announcements made on Liberation Day (2 April), namely a tariff of around 25% on the world and of 145% on China, the de-escalation has been vertiginous. But to assess the impact of the shock, the true point of comparison should be the tariff level before ‘Trump II’. Taking into account current exemptions and suspensions, the average tariff applied by the US is approximately 14% vs just under 3% in January, a fivefold increase.

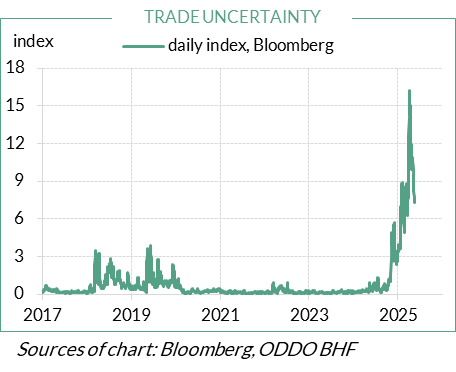

The method: in reality, there is no clear method. In Trumpian circles, attempts have been made to rationalise the president’s series of actions by placing them within a well-thought-out plan whose components will become clear to everyone else over time. This is unconvincing and frequently pathetic. Trump’s economic policy is intrinsically unpredictable. Recent trade “deals” signed with the UK (8 May) and China (12 May) are not legally binding. They are deeply asymmetrical and violate one of the underlying rules governing world trade (the most favoured nation clause). Who can guarantee that the conditions of these deals will not be modified within a few months? During the US-China trade war of 2018-2019, there were three phases of tensions before a final agreement was reached. Uncertainty indices have fallen sharply in the past month, but they remain high by historical standards and there is no reason for them to return to their initial position (Chart).

What were economic conditions immediately prior to the “Trump shock”? At the start of 2025, world growth stood at 3.2% and had been stable there for several years. After its surprising strength in 2023 and 2024, the US economy looked likely to surpass its potential again in 2025. The eurozone was showing a few signs of recovery, albeit unevenly spread between countries, with Germany still lagging behind. Chinese growth was dampened by the weakness of domestic demand and was primarily dependent on external trade. World inflation remained on a downward trajectory, a result combining persistent strains in the US, deflationary forces in China and normalised inflation in Europe.

What is the nature of the “Trump shock”? In the US, it takes the form of a negative supply shock, since it involves mechanisms that are weighing on both employment and spending (uncertainty, financial conditions and trade disruption) and raising production costs and prices. Tariffs are paid by importers in the countries imposing them and are mostly passed onto retail prices in the domestic market. It is an illusion to think that exporters will trim their margins to compensate. In Europe, where retaliatory tariff measures have been moderate, and in China, where domestic demand is already weak, the negative impact on demand is likely to predominate, with few notable repercussions on prices.

What are our forecasts in this context? These days, any forecast has a limited shelf life and will change according to the degree of uncertainty and tariff stress. In mid-April, at the height of US-China tensions, it was hard to see how these two countries could avert a recession in the coming year. Three-digit tariffs constituted a sort of embargo and the expected collapse in bilateral trade could have caused a loss of up to 2pts of GDP in China and 0.5pts in the US, without taking into account the negative repercussions on investment and hiring decisions. One month later, the de-escalation (assuming it is lasting) has lowered the probability of this scenario to around 40%, on our estimates, still double the historical average. In the eurozone, several factors remain conducive to a recovery: receding inflation, recovering bank lending and the resilience of the job market. But any acceleration is more likely to materialise in 2026 when the fog has lifted and the new German government has launched its fiscal stimulus.

What will the monetary policy reaction be? It depends on the nature of the shock. The Fed is in the most uncomfortable position, since the risk of stagflation can in theory justify conflicting decisions: loosening if unemployment rises, or tightening if inflation expectations spiral. In doubt, the Fed is holding fire, but recent comments by its officials show that the principal preoccupation today remains the inflation mandate. The next three meetings may result in a status quo, like the three previous ones. The ECB does not have this dilemma. With inflation back at its target and the euro appreciating, it still has a little scope to loosen monetary policy.

Disclaimer

This document has been prepared by ODDO BHF for information purposes only. It does not create any obligations on the part of ODDO BHF. The opinions expressed in this document correspond to the market expectations of ODDO BHF at the time of publication. They may change according to market conditions and ODDO BHF cannot be held contractually responsible for them. Any references to single stocks have been included for illustrative purposes only. Before investing in any asset class, it is strongly recommended that potential investors make detailed enquiries about the risks to which these asset classes are exposed, in particular the risk of capital loss.

ODDO BHF

12, boulevard de la Madeleine – 75440 Paris Cedex 09 France – Phone: 33(0)1 44 51 85 00 – Fax: 33(0)1 44 51 85 10 –

www.oddo-bhf.com ODDO BHF SCA, a limited partnership limited by shares with a capital of €73,193,472 – RCS 652 027 384 Paris –

approved as a credit institution by the Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR) and registered with ORIAS as an

insurance broker under number 08046444. – www.oddo-bhf.com